Rapid Softlithography Using 3D‐Printed Molds

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) is a long‐standing material of significant interest in microfluidics due to its unique features. As such, rapid prototyping of PDMS‐based microchannels is of great interest. The most prevalent and conventional method for fabrication of PDMS‐based microchips relies on softlithography, the main drawback of which is the preparation of a master mold, which is costly and time‐consuming. To prevent the attachment of PDMS to the master mold, silanization is necessary, which can be detrimental for cellular studies. Additionally, using coating the mold with a cell‐compatible surfactant adds extra preprocessing time. Recent advances in 3D printing have shown great promise in expediting microfabrication. Nevertheless, current 3D printing techniques are sub‐optimal for PDMS softlithography. The feasibility of producing master molds suitable for rapid softlithography is demonstrated using a newly developed 3D‐printing resin. Moreover, the utility of this technique is showcased for cell culture (to show biocompatibility of the process) and other applications. [...]

Please register below to read the full article digest.

Introduction

There is a growing body of literature that recognizes the significance of lithography in the fabrication of PDMS‐based microchannels. However, lithography is limited in its ability to fabricate non-straight microchannels. Therefore, research groups have tried to provide alternative methods for the fabrication of molds used in softlithography processes.16 One such alternative is the use of 3D printing technology for the fabrication of softlithography molds. Among all 3D printing methods, stereolithography apparatus (SLA) and digital light processing (DLP) offer great advantages, making them ideal candidates for microfluidics and biomedical applications.17 However, one of the limitations of 3D printed SLA/DLP master molds for softlithography is the requirement for tedious pretreatments prior to PDMS casting. The pretreatment of the resin is necessary to ensure the complete curing of the PDMS in contact with the resin. Otherwise, the surface of the PDMS replica in contact with the resin cannot be polymerized due to the presence of residual catalyst and monomers, and its transparency would be also compromised.18 It has been observed that the effects of pretreating the master mold are more significant in channels with smaller feature sizes,19 and, in the case of relatively larger 3D printed parts, this challenge is not significant.20 To address this issue, many researchers have proposed various pretreatment protocols to treat the 3D printed master mold before PDMS casting.18, 19, 21-24

Four procedures are commonly used among other proposed post-printed protocols: 1) UV curing; 2) surface cleaning (e.g., ethanol sonification and soaking); 3) preheating; 4) surface silanization. Waheed et al. introduced an efficient yet time‐consuming pretreatment protocol for PDMS softlithography.24 The postprocessing included a 5 min UV treatment followed by 6 h of soaking in an ethanol bath. Following the air plasma treatment for 1 min, the surface of the 3D printed template was silanized by perfluorooctyl triethoxysilane for 3 h. Nevertheless, there is still no consensus about the optimum protocol for treating 3D printed templates for PDMS casting. In addition, the proposed protocols are time‐consuming, labor‐intensive, and lacking reproducibility. Furthermore, the treatment parameters, such as UV curing time, preheating temperature, and duration, seem to be a function of the feature size; thus, differ from one experiment to another.24 Also, preheating in particular is a common step in many procedures and often induces high levels of material strain, resulting in the formation of cracks within microstructures.18, 25 Most importantly, surface silanization of the 3D printed templates is essential to ensure the PDMS peels off, correctly. Some silanizing agents such as perfluorooctyl triethoxysilane are cytotoxic and are not suitable for biological applications. Thus, development of a resin suitable for master mold fabrication will reduce all these time‐consuming steps.

To address the aforementioned issues, herein, we optimize the use of a new resin developed by Creative CADworks (CCW Master Mold for PDMS devices) (i.e., made of methacrylated oligomers and monomers) for the fabrication of master molds directly by the DLP 3D printing method. We show that the 3D printed templates obtained using this resin can be immediately casted with PDMS without any pretreatment or surface modification. By way of explanation, the process of master mold design to microchip fabrication has been reduced from a time frame of several days (for a conventional softlithography process) to less than 5 h. In order to showcase the functionality of this resin, four different microfluidic devices have been developed. Each device represents a specific application, including separation, micromixing, concentration gradient generation, and cell culturing. The surface of the PDMS replica obtained from the 3D printed mold is also evaluated to investigate the bonding quality of PDMS.

Methods

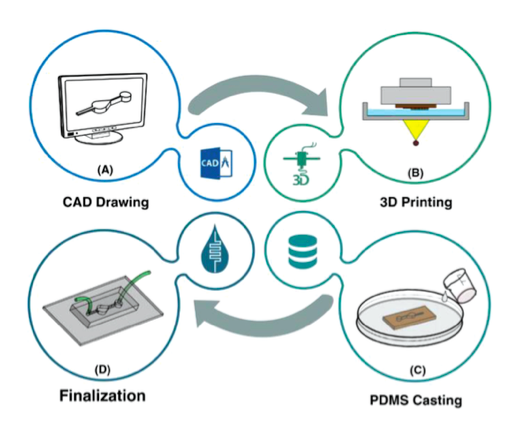

PDMS Casting:

The workflow of the master mold preparation by DLP/SLA 3D printing method and microfluidic resin. A) The desired master mold is drawn. The beauty of microfluidic devices is that they require neither intricate geometries nor professional CAD drawer. Thus, the CAD drawing process will not take a long time. B) The design is then printed using a DLP/SLA 3D printer, and the residuals are removed from the surface of the mold. C) Afterward, PDMS is poured in the master mold, and D) in the final stage, PDMS is peeled‐off, bonded to a glass or PDMS layer, and the finalization followed by the installation of inlets and outlets.

Surface Characterization: Surface characterizations of the 3D printed mold and PDMS were analyzed using 3D laser microscopy (Olympus LEXT OLS5000); to this end, an LMPLFLN 20× LEXT objective lens (Olympus) was selected. Arithmetic mean deviation (Ra), the arithmetic mean of absolute ordinate Z (x,y) documented along a sampling length, and arithmetical mean height (Sa), the arithmetic mean of the absolute ordinate Z (x,y) documented along an evaluation area were chosen to evaluate the surface characterization of the samples.

Results

PDMS Characterization

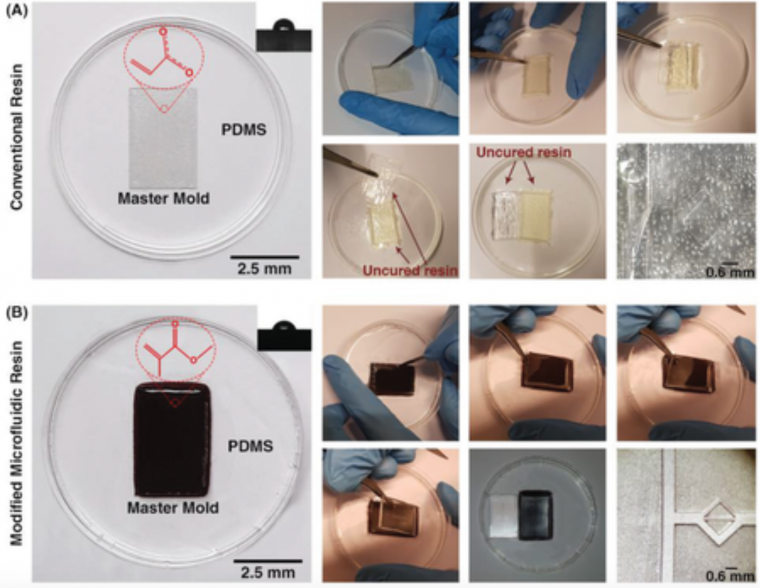

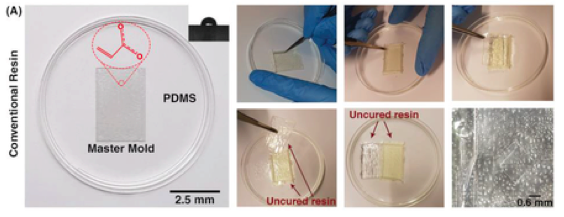

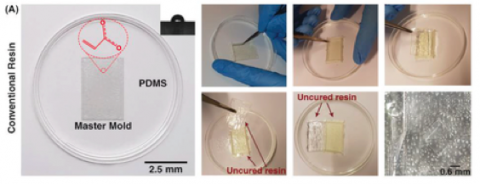

It is well‐known that the quality of the PDMS casted on the mold can affect the whole performance of the microfluidic device.26 Hence, its quality must be analyzed before use. After fabricating the 3D printed molds and removal of any residual resin, PDMS was casted on the master molds. For the sake of comparison, two different molds were fabricated, one with a conventional DLP resin and the other with the newly developed microfluidic resin. The main challenge with conventional DLP resin is that due to the presence of unreacted monomers, complete polymerization of PDMS cannot occur, resulting in the presence of residual material on both the PDMS and the mold. The comparison between the mold fabricated via conventional resin and the microfluidic resin reveals that these two molds have identical surface roughness, and the smallest channel height for the fabrication of molds can be achieved with a thickness layer of 30 µm. However, for this thickness layer, the curing time of each layer for the newly developed resin is 6.5 s, which is more than the conventional one which is 1.3–1.5 s; as more time must be devoted to the methacrylated resins to be completely polymerized and cured. All in all, the fabrication time for both molds took less than an hour which is much faster than other methods.

Also, the inset in Figure 2A shows the contact angle of the 3D printed molds. The contact angle measurement reveals that both surfaces are hydrophilic; however, the microfluidic resin is slightly more hydrophilic than the conventional one.

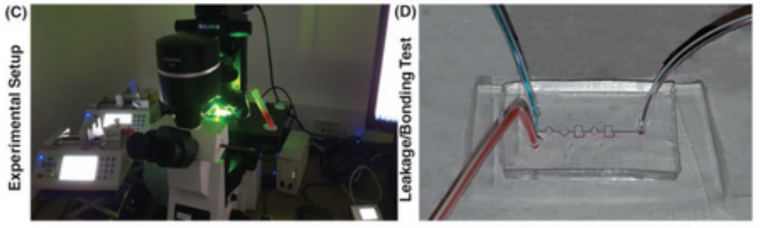

Figure 2

PDMS casting process in A) conventional DLP resin and B) microfluidic resin. The insets depict the contact angles on the surface of molds. In conventional resin, PDMS in touch with the surface of the mold cannot provide a temporary bonding, and the surface of the PDMS cannot replicate the pattern used in resin. In microfluidic resin, as soon as the blade reaches the surface of the mold, PDMS start to detach from the surface, and it can easily peel‐off. The mold after PDMS casting in microfluidic resin clarifies that there is not any residual of PDMS on its surface, while in conventional DLP resin, residuals are on the surface. C) Experimental setup used in these series of experiments is illustrated. D) No leakage was seen during the experiments after bonding of PDMS by plasma surface treatment method.

As Figure 2A indicates, in the conventional DLP resin, PDMS surfaces in contact with the surface of the resin were not properly cured, and uncured PDMS layers remained on both surfaces. It can be clearly seen that the casted PDMS fails to adopt the pattern of the mold, thoroughly. In addition, during the detachment of PDMS from the mold, PDMS tends to stick to the resin, confirming that the surface of the conventional DLP resin is not appropriate for PDMS casting. By analyzing the materials constituting the conventional DLP resin, it is believed that this problem is related to the chemical composition of the resin. We hypothesized that the remaining catalyst and monomers on the surface of the printed mold disrupt the complete polymerization of a thin layer of PDMS in contact with the mold. This can be clearly seen upon the removal of the PDMS replica from the mold (Figure 2A). As such, the “acrylate group” in the resin's chemistry is not a suitable choice for PDMS casting; this has urged different scientists to explore time‐consuming strategies for the surface treatment of DLP printed molds. Through extensive research conducted by Creative CADworks, a new resin which contains methacrylated monomers and oligomers has been developed. Casted PDMS does not react with the methacrylated monomers because the surface of the mold is free of residual monomer units that may impede PDMS polymerization. As Figure 2B illustrates, once a blade cuts through the PDMS layer down to the mold, the PDMS replica detaches easily. The operation of each device and the quality of bonding were also analyzed for a wide range of flow rates (to check the simulations results of surface roughness and bonding quality, see Section 2.2) with the experimental setup shown in Figure 2C. The results, as shown in Figure 2D, confirmed that there was no leakage observed between flow rates ranging from 0.1 to 5 mL min−1, which indicates that the proposed method for fabricating PDMS‐based microdevice is an ideal candidate for a variety of applications.

As Figure 2A indicates, in the conventional DLP resin, PDMS surfaces in contact with the surface of the resin were not properly cured, and uncured PDMS layers remained on both surfaces. It can be clearly seen that the casted PDMS fails to adopt the pattern of the mold, thoroughly. In addition, during the detachment of PDMS from the mold, PDMS tends to stick to the resin, confirming that the surface of the conventional DLP resin is not appropriate for PDMS casting. By analyzing the materials constituting the conventional DLP resin, it is believed that this problem is related to the chemical composition of the resin. We hypothesized that the remaining catalyst and monomers on the surface of the printed mold disrupt the complete polymerization of a thin layer of PDMS in contact with the mold. This can be clearly seen upon the removal of the PDMS replica from the mold (Figure 2A). As such, the “acrylate group” in the resin's chemistry is not a suitable choice for PDMS casting; this has urged different scientists to explore time‐consuming strategies for the surface treatment of DLP printed molds. Through extensive research conducted by Creative CADworks, a new resin which contains methacrylated monomers and oligomers has been developed. Casted PDMS does not react with the methacrylated monomers because the surface of the mold is free of residual monomer units that may impede PDMS polymerization.

Biological Applications

In vitro cell culture platforms play a crucial role in cell biology, cancer research, regenerative medicine, pharmacy, and biotechnology. Although 2D cell culture in planar dishes is still widely used, this oversimplified model fails to mimic the actual cellular microenvironment.

Alternatively, 3D cell culture platforms (mostly in the form of multicellular spheroids) are far more realistic models, which can better mimic in vivo responses.39 However, these static 3D systems are still sub‐optimal and lack many of the critical features essential to a complex tissue microenvironment. Additionally, these systems cannot precisely control the chemical and nutrient concentration gradients over time and space. Furthermore, the oxygen tension and shear stress experienced by the cells are different from in vivo conditions.40 To address these shortcomings, microfluidic 2D and 3D cell culture platforms have emerged recently, progressing along with the rapid advances in microfabrication techniques.41 Such platforms offer several advantages to engineering a physiologically relevant biomimetic tissue.

Here, we chose a pear‐shaped microchamber similar to the design proposed by Chong et al.42 The authors used the pear‐shaped design to minimize the shear stress during continuous perfusion.

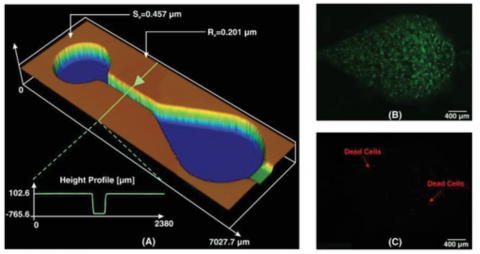

To fabricate the arrays of the microchambers, Liu et al. used standard dry etching on a silicon substrate followed by PDMS softlithography. The dimensions and characteristics of the 3D printed microchamber are shown in Figure 5A. The total printing time starting from the initial design to the final product took only 45 min. MCF‐7 cells with a concentration of 106 cells mL−1 in culture media (Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% streptomycin–penicillin) were introduced into PDMS microchamber. The device was incubated for 24 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. To evaluate the cell viability in the PDMS microchamber, live/dead cell double staining was performed. As shown in Figure 5B,C, more than 98% of the cells remained viable in the microchamber 24 h after the initial cell seeding. This confirms that no cytotoxic residual material had been left on the PDMS from casting on the 3D printed resin. Also, in cell culture platforms, flow rates exist in the order of µL min−1,43 and the values of Ra and Sa, as shown in Figure 5A, indicate that the device is functional within its flow regime. Therefore, it can be concluded that the newly developed resin for 3D printing master molds is suitable for cell culture applications and does not compromise cellular viability. Currently, lung‐on‐a‐chip studies using 3D printed microfluidic resin molds are under investigation in our group; these studies demonstrate long‐term cell viability (more than a week).

Figure 5

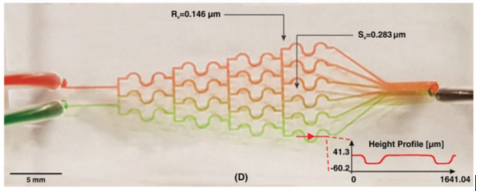

A) Whole‐chip image of the cell culture device with its related Sa, Ra, and height profile. B) Live and C) dead images of the cells after 24 h incubation, which show that cell viability in these devices are noticeable, and total numbers of dead cells are rare. D) Concentration gradient profile of two food colors of red and green. The results reveal that the newly developed microfluidic resin is suitable for cell culture applications.

Discussion

The gradient of biomolecules plays a crucial in controlling various biological activities, including cell proliferation, wound healing, and immune response. One of the most popular types of CGGs that produces discontinuous concentrations is the tree‐like CGG. This type of CGG is based on the fact that one can divide and mix the flow through bifurcations and pressure differences downstream. This type of CGG is usually used for cancer cell cultures, as these CGGs transfer more oxygen and nutrients to cells as they develop a convective mass flux. Among various tree‐like CGGs proposed in the literature, we chose the S‐shaped CGG design developed by Hu et al.44 The authors used micromilling to fabricate the CGG on a polymethylmethacrylate substrate. Here, we developed the same structure in PDMS using softlithography based master mold fabrication from our new microfluidic resin. Figure 4D shows the characteristics of the fabricated CGG. The device has two inlets and six outlets to produce six different concentration ranges. To examine the performance of the device, we used two colors of food dyes (please refer to the Supporting Information for dye preparation protocol). The concentration profile of the fabricated CGG is illustrated in Figure 5D, which is similar to those reported by the literature.44 Since the velocity in CGG devices is small,45 surface roughness cannot impose problems on the binding of PDMS. For printing of planar structures, 3D printing can be performed with higher slice thickness, as a result of which, printing time will be reduced.

In summary, the microfluidic resin for 3D printing is an ideal candidate for fabricating different bio‐microfluidic devices and can replace all cost‐intensive and time‐consuming fabrication methods.

Conclusion

In this study, we introduced a microfluidic resin for direct fabrication of master molds for PDMS softlithography, which can substitute other time‐consuming master mold fabrication methods. Conventionally, the main components of SLA/DLP resins are acrylated monomers and oligomers. These materials cannot provide a temporary attachment to PDMS without leaving uncured PDMS on the surface of the mold, indicating that the PDMS cannot replicate the mold pattern. In the proposed master mold microfluidic resin, methacrylated monomers and oligomers have been used to facilitate PDMS casting, the proof of which was illustrated by fabrication of four benchmark microfluidic devices, including separator, micromixer, cell culture device, and a concentration gradient generator. In addition, the effects of velocity and shear rate distribution on the total performance of the microfluidic device were investigated numerically. It was shown that the surface roughness has to be small enough so as to not create extra shear stress endangering PDMS bonding. As the fabricated devices were tested in wide ranges of Re, we showed that there was not any leakage in these microfluidic devices. The height profile also confirmed that there was not any major discrepancy between the CAD geometry and the fabricated part. The results of the spiral microchannel for flow rates from 0.5 to 3 mL min−1 illustrated that the behavior of particles in spiral microchannel was in line with those reported in the literature, and the microchip could withstand high flow rates. The characterization of the micromixer also demonstrated that the proposed microfluidic resin was able to fabricate microchannels with different geometries, and the mixing result was appealing so that two tested color dyes mixed completely. In the conventional softlithography process, silanization is necessary to prevent the attachment of PDMS to the master mold, which can be detrimental for cellular studies. The 3D printed mold obtained from the microfluidic resin proposed here does not require any silanization, and the cellular studies in the PDMS‐based cell culture device confirmed the biocompatibility of the resin. The 3D printed CGG device produced a stable gradient profile, implying the application of such a versatile 3D printing technique for effective drug delivery. As PDMS‐based microchannels are ubiquitous in microfluidic devices, the present study can be considered as a milestone in the microfluidic field which can reduce the brainstorming‐to‐production from a time frame of several days (including the time required for conventional master mold fabrication and post‐treatment) to less than 5 h (with the new proposed microfluidic resin).